2016-17

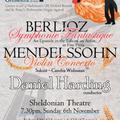

Sunday 6th November 2016, Sheldonian Theatre

Conducted by Daniel Harding

Featuring Carolin Widmann

Led by Elizabeth Nurse

Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique

Mendelssohn Violin Concerto

Charity concert in aid of Parkinsons UK and St Peter's Church, Wolvercote, Organ Appeal

A review of this concert can be found here:

Review: Oxford University Orchestra play Mendelssohn and Berlioz – The Oxford Culture Review

Oxford University Orchestra‘s Christmas concert was one of the most anticipated that Oxford University had seen in years, featuring two much-loved works (Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto), with two illustrious guests. One was conductor Daniel Harding, Music Director of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Principal Guest Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, who has conducted both the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic, among notable others. The other was the award-winning violinist Carolin Widmann, who has previously performed as a soloist alongside conductors including Simon Rattle and Sir Roger Norrington. Sitting waiting for the (somewhat late) start, it was hard not to wonder whether the concert could possibly live up to expectations.

The main focus of Widmann’s career has been contemporary avant-garde music, so Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, a seminal Romantic work, is a far cry from her usual fare. On the one hand, her technical abilities shone as she deftly handled the virtuosic cadenzas, demonstrating the level of technical skill which allows her to play extraordinarily demanding contemporary music. Her tone, however, was rather stark. While this may be ideal in abstract modern compositions it wasn’t well suited to the richly emotive Mendelssohn, although in places it did allow a beautifully reflective quality to come through. It also meant that at times the solo violin sound was drowned too easily by dramatic orchestral crescendos, rather than growing to the climax with them.

The orchestra brought great vigour to their interjections and accompanied Widmann with impressive control, not drifting out of time even in the busiest passages of the final movement. The strings made a full sound, and the woodwind solos were expressively rendered. This work is all about the violin though; neither the orchestra nor the conductor makes or breaks it. Their performance here was perhaps best described as “solid” — a word which also aptly describes Widmann’s performance. It was nicely phrased and perfectly in tune throughout, without a note out of place, but it somehow felt “well rehearsed” rather than “fantastic”, lacking in the tiny expressive details which take the ear by surprise, and a performance to the next level. The second movement was attractive, but lacked the heart-rending beauty lent to it by David Oistrakh’s sonorous tone in his recordings, while the witty and fun nature of the third movement could have come across much more strongly, as it does in Maxim Vengerov’s performances of the work. Widmann took the same unsentimental approach one would take to Boulez which, for me at least, wasn’t a good fit with such an expressive work.

If the first half of the concert could have benefitted from more character, this was certainly not the case in the second half. From the opening moments of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique Daniel Harding’s ability to bring a piece to life shone through. Not only did he demonstrate superb control of tempi, rubato, and balance, he also gave the orchestra constant signals about the music’s mood. Assistant conductor David O’Neill, who took most of the rehearsals, had clearly rehearsed the orchestra thoroughly, no doubt deserving credit for much of the good phrasing, attention to dynamics, and outstanding level of ensemble, but Harding’s distinctive conducting visibly galvanized the orchestra into playing with real energy on the night.

The orchestra must be given considerable praise for the way they were able to respond to Harding’s every whim. The strings shone particularly in the first two movements (‘Reveries’ and ‘Un bal’), achieving a standard of ensemble, dynamic range, and flexibility not often found in student orchestras, particularly those of this large size. The third movement featured a notable performance from cor anglais player Chloe Barnes, whose playing oozed confidence and class during the opening duet with the offstage oboe (which signifies two shepherds playing to each other across a valley). The brass had (and clearly enjoyed) their moment of glory in ‘March to the Scaffold’, a tune it is impossible not to raise a smile for. As the Symphony reached its morbid conclusion in the Dance of the Sabbath’s ‘diabolical orgy’ (as Berlioz described it), there was some fantastically garish E-flat clarinet playing from Dan Mort, before an ending so loud that it raised concerns for the wellbeing of the Sheldonian roof.

What came across most strongly at the end of the concert was that the orchestra had, both literally and figuratively, had a blast. After a first half in which personality seemed to have been sacrificed for technical achievements, the second half was full of vitality and, frankly, more enjoyable than many professional performances. At a time when classical music is increasingly hostile to anything other than technical perfection, it demonstrated the great (and often forgotten) importance of just having fun.

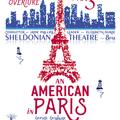

Saturday 11th February 2017, Sheldonian Theatre

Conducted by Jamie Phillips

Led by Elizabeth Nurse

Copland Symphony No.3

Gershwin An American in Paris

Bernstein Overture from Candide

A review of this concert can be found here:

Oxford University Orchestra Hilary Term Concert - Daily Info | Daily Info

An American far from home in Paris

Guest conductor Jamie Phillips was in Stoke-on-Trent on Friday, conducting Haydn, Mozart and Sibelius, and here he was on a cold Broad Street evening pursuing the peripatetic life of the professional musician by overseeing an all-American programme from the Oxford University Orchestra, with Leonard Bernstein's fingerprints all over it. The latter wrote the first programmed work, the opera Candide in the fifties, and we heard its overture, as usual in this abbreviated form of music replete with the tunes to be heard in the body of the work, and getting us off to a rousing start. The basis for these student programmes is, I take it, to choose colourful works requiring a numerous orchestra with opportunities for the discrete sections to shine, and this rationale was here perfectly fulfilled. The orchestra filed in as a body and received a cheery round of applause by the swelling audience that comprised largely friends and adherents of the players. Mr Phillips announced his style on the podium, bursting with energy and expansive gestures.

The second work before the interval, An American in Paris, is a jazz-tinged symphonic poem by George Gershwin from 1928, and much admired by Bernstein. To those sniffy critics unwilling to allow an upstart composer of jazz and dance works into the hallowed halls of serious music, Gershwin responded: "It's not a Beethoven Symphony, you know... it's a humorous piece... if it pleases symphony audiences as a series of impressions, it succeeds." Inspired by the period when the composer was living and studying in Paris, it evokes the sights and vitality of the 1920s city.

The orchestra now numbered 90-odd, boosted by saxophones, additional percussionists and a set of pseudo-Parisian taxi horns, striving - successfully - to convey a bit of the atmosphere of the Grands Boulevards and the Quartier Saint-Germain des Prés. A jazzy, Broadway musical feel was immediately established in episodes of bustling urban activity punctuated by the stereophonic squabbling of the horns, with brief, hazy visions of peaceful gardens perhaps of the Tuileries and the Jardin du Luxembourg.

Individual players now laid out their credentials. We had a plangent solo from oboist Matt Jackson, swinging his body to the music, some vigorous arpeggios from the double bass section, and in the penultimate bars we heard from the three trombones, with Robert Ham's tuba playing a booming little solo. In the famous Paris by Night section with its violin cadenza that leads into the famous trumpet bluesy passage, a queasy sense swirled round the hall of the homesickness of our American friend far from home in Europe. Soon, though, we are drawn to the hooded lights of a Jazz Club, smoky and sleazy with saxophones.

Aaron Copland's Third Symphony of 1946, distinguished by Leonard Bernstein's definitive recording of 1966, is scored for an equally numerous orchestra, including upright piano, piccolo, cor anglais and cabin-trunkfuls of percussion exotica, played by eight multi-tasking musicians. In the stately beginning, Mr Phillips was adept in his shaping of the opening string lines, based on repetitive quarter notes, in long arcs. He later built the big climaxes with a firm hand, the brass sounding clarion calls that were never harsh. My eye was repeatedly caught by timpanist Ben Varnum standing over his drums, crouching like a tiger about to spring from its jacaranda tree onto a hapless goat tethered to a tree below, crashing down his drumsticks in the crescendos, a picture of intense concentration.

I thought I detected a touch of Shostakovich in Mr Phillips' pointing of the quirky twists in the boisterous 'allegro molto', a big contrast to the 'andantino' with its eloquent, thoughtful string playing what is perhaps the heart of the symphony, giving full expressive force to Copland's darker moments. Here, as earlier in the 1st movement and later in the finale, we heard the expressive flute of Calla Randall. In the latter section, Copland's famous Fanfare for the Common Man anthem is first heard in low-key form from the flutes before ringing out triumphantly from the brass and then being tossed between them and the strings with help from the potent percussion battery.

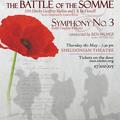

Thursday 18th May 2017, Sheldonian Theatre

Conducted by Ben Palmer

Led by Victoria Gill

The Battle of the Somme, 1916 film by Geoffrey Malins and J.B. McDowell

with new score composed by Laura Rossi, performed alongside live screening

as part of the Somme100 FILM project (somme100film.com)

Vaughan Williams Symphony No.3