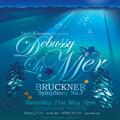

Trinity 2016

Saturday 21st May 2016, Sheldonian Theatre

Conducted by Robin Browning

Led by Elizabeth Nurse

Bruckner Symphony No.7

Debussy La Mer

A review of this concert can be found here:

Oxford University Orchestra - Daily Info | Daily Info

And a Robin Browning interview article in the Oxford Student with James Chater can be found here:

Interview: Robin Browning – The Oxford Student

Interview with the Oxford Student | Robin Browning

Debussy and Bruckner from an energetic young orchestra, galvanised by their conductor

The Oxford University Orchestra's termly concerts are always fun and usually challenging. The challenge on Saturday was manifest: the unusual programming of Debussy's La Mer, probably the most important musical work of French Impressionism and which introduced non-functional harmony to orchestral music, with Bruckner's 7th Symphony, one of his massive cathedrals of sound.

Work on La Mer was started in 1903 in France and completed in 1905 at the Grand Hotel, Eastbourne, then in its Edwardian heyday. The composer corrected the proofs there between 24th July and 30th August 1905 in Suite 200, now known as the Debussy Suite. The hotel lies on the seafront and from his suite Debussy would at night have looked directly out to the winking light of the Royal Sovereign lightship, moored 11 miles off the coast.

The 1st movement, 'Del'aube à midi sur la mer', has a lilting ebb and flow as of the tide, played with a fine sensitivity that brings out many of Debussy's little orchestral details - shimmering cymbals and tinking xylophone, for example (behind her instrument, the xylophonist Miranda Davies kept up a restrained little jig to the music throughout the piece - nice!). Is it fanciful to wonder whether this tinking represents the pinpoints of light out in the English Channel? Conductor Robin Browning, the sole professional musician present, held the tension so that, when the final climax bursts out, it is magnificent, a great surge of the waves. The concluding 'Dialogue du vent et de la mer' contained some exquisitely still moments, particularly when the flute and oboe played over hushed strings.

Mr Browning's conducting was a visual delight throughout the programme. Such smooth co-ordination of baton and free hand, such sea-breeze swaying of his whole body, the kind of elegant movement that Debussy himself must have witnessed at waltz-time in the ballroom of the Grand Hotel. No chopping gestures, no fussy micro-management of his players. Then, at the crescendos, he was suddenly galvanised, giving out waves of energy to his young orchestra - an inspiring sight. One could imagine the atmosphere of disciplined good humour in which those rehearsals must have been held.

After the interval came the Bruckner, a daunting prospect for amateur players, and not least by virtue of its great length (over an hour). Mr Browning told me after the concert that he'd had the orchestra for four rehearsals over a two-week period - the bare necessary minimum, I'd have thought - and what a joy it was to collaborate with young people so quick to learn and to remember. The opening bars immediately bring Wagner's Siegfried's Lament to mind and Mr Browning produced the characteristic Bruckner feeling of spaciousness, as though one were atop a high peak, surveying a limitless horizon.

The brass section now numbered 15 to the wind section's eight, rather an imbalance. Four of the former were a novelty, Wagner tubas, a sort of hybrid between a horn and a trombone. These weighed in where the score was punctuated by hammer-blow climaxes. That said, their presence led, I thought, to the one infelicity all evening where towards the end of the adagio at the second grand climax, a famous one, from which the orchestra descends to a peaceful threnody, the strings were swamped by the force of the brass. Elsewhere, I appreciated the flute solos from Elias Tomarkin and the trumpet of Fifi Korda.

My post-concert thought was when next are we to hear Robin Browning conduct in Oxford?

Back in May I was invited to conduct one of the top student orchestras in the UK – Oxford University Orchestra. Our performance in Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre of Bruckner’s 7th Symphony, coupled with Debussy’s La Mer, prompted rave reviews (more of these later) and an almost immediate re-invitation. In terms of their scheduling, it was nice to be sandwiched in between such esteemed company as Daniel Harding and Hugh Brunt, as it were.

As part of the pre-concert publicity, I gave an interview with the Oxford Student newspaper. As you can imagine, being Oxford, this was a little more probing than a many interviews often are – full of erudite questions, and possibly even some erudite answers (I hope). Despite the event being a few months ago, I thought the Q&A is worth reproducing here.

With many thanks to James Chater and OxStu magazine

On Saturday 21st May 2016, Robin Browning will conduct the Oxford University Orchestra (OUO) in Debussy’s masterpiece La Mer and Bruckner’s Symphony no.7 in E Major at the Sheldonian Theatre. Robin is an established conductor, performer and music-educator. Praised as an “expert musician and conductor” by Sir Charles Mackerras, he is a passionate advocate for music and for the arts in general.

In the interview, Robin speaks to OxStu about working with OUO, the repertoire they will perform, and his admiration of Bruckner.

This the first time that you’ve conducted OUO; are you excited about the prospect of working with the orchestra and in Oxford?

Very much so. I know OUO have a history of inviting fine, established conductors to work with them as guests, and it’s great to be in such good company. I felt sure it would be a strong orchestra – quick-witted, aware and flexible – even after one rehearsal this turns out to be true. I regret to say I know Oxford far less than I should – it’s only my third visit – but I hope this will change.

With OUO, there’s a fairly short period of rehearsing with an orchestra you don’t know. What are the particular challenges and benefits associated with this type of preparation?

In many ways I prefer it – it limits the amount of time one can faff about, and focuses the mind! I’m a firm believer that, unless you’re Carlos Kleiber, a conductor’s work always seems to expand to fill the time available. Having said that, you need good players who respond well and think enough in between rehearsals, too. It’s similar to what one expects with professional orchestras – fewer sessions, clumped together shortly before the gig.

Perhaps, going on from that, what do you enjoy most about working with students?

Open, inquiring minds. Quite apart from the considerable talent within the orchestra, I’ve already sensed a generosity of spirit from the ensemble as a whole. This isn’t always the case – either with students or pros. With OUO, I get the impression that every single player wants it to be a really strong performance.

Arguably, the two works we’ll be performing couldn’t be aesthetically further apart. Firstly, how do you think they’ll complement each other?

It’s fascinating. They’re kind of odd bedfellows, but I think they work well. Bruckner can appear so formal, monolithic and weighty. I used to programme his music with other Austro-Germanic music (Wagner, Strauss, etc) and it can all get a bit much. Debussy is another world entirely. Plus, despite the apparent contrasts, there are subtle similarities when one comes to rehearse them side-by-side: there’s more of a “modular” side to Debussy than one might think…

Secondly, what are the performative difficulties associated with moving between Debussy and Bruckner?

One must take care to find the other world, to breath the “new” air when crossing between the two of them. There are enormous differences in colour and timbre, of course – but also in the way one has to breathe, where one chooses to centre the sound, and how to balance and structure chords – they must all be approached differently. Ultimately, as a conductor, I must be clear to inhabit the appropriate world and not let one bleed through into the other, and strive to bring the orchestra with me in that regard.

What is it that makes Debussy’s style of impressionism distinctive for you?

I think particularly the use of light. He not only finds a breath-taking array of colours, but dances with the interplay of light, pretty much throughout La Mer. Like a series of brushstrokes, his rhythmic cells, dabbed across the entire orchestra, create a constantly shifting aural tableau which is then viewed from different angles, each time with different light. It’s not just the sea he captures in La Mer – he also captures the changing light.

Critics have also noted that the score of La mer in many ways anticipates those of film scores. Do any particular episodes from la mer strike you as such?

Well, I guess all those colours can easily be re-purposed for film. In truth, it doesn’t strike me so overtly like film-music, perhaps apart from some general tones and colours. The Bruckner does far more so, to me – harmonically so, and in terms of instrumental colour, for example strings and horns: think John Barry or Hans Zimmer (depending on circumstance)

Debussy resisted calling the work a symphony outright – but many since have labelled it as such? How do you think it resists or perhaps even supports such a label?

In that way it’s a curious juxtaposition in this concert, being placed with Bruckner – something we’d regard as a “typical” symphony. Whilst La Mer may embody the true original meaning of the word, being as it is packed full of sounds and motifs, all developing organically, I don’t view it symphonically

From just one rehearsal with you it was clear that you have a particular affinity with Bruckner. Could you briefly sum up why that is in a few sentences?

Harmony. Pure and simple. Yes, there’s FAR more to Bruckner than that, I know. But most conductors are harmony geeks (I certainly am) and he accesses parts of the brain – and heart, if you like – that few others reach. Plus there’s this naivety in a lot of it, coupled with melancholy (not quite as much as Elgar – no one’s in that league) which I find desperately touching.

You mentioned a striking relationship between Bruckner and Schubert – immediately after you said that, a lot of the music suddenly made sense to me (the shifts in harmony particularly) – could you describe the effect and how Bruckner achieves this?

It’s about seeing Bruckner as the natural heir to Schubert, rather than Wagner, despite the obvious connections between the 7th and his idol. Because his writing can be (superficially) so “blocky”, many interpreters sacrifice his extraordinary sense of line, and the shifts of colour and balance he creates throughout such long spans become lost. One often hears a monolithically sculpted edifice of sound. This, to me, is more suited to Shostakovich – and maybe the early Bruckner symphonies where his architectural sense is less developed.

Finally, what is it that individuates Bruckner 7 from his other symphonies?

Maybe it’s light – and how appropriate that is, when we’re coupling it with La Mer. He lets more light shine through this symphony than the others which surround it, and that’s apparent right from the very opening bars: bright, radiant and somehow incandescent to the symphony’s very end.